The Tragedy of Suicide

- Odell Terrell

- Aug 3, 2021

- 7 min read

Updated: Aug 4, 2021

Not Just a Public Health Crises:

We all know suicide is on the rise. And it is not just because of the COVID pandemic, where we have seen five times more death by suicide since the beginning of the pandemic than the virus itself on our youth.

The rise of suicide has been well documented for the last several decades. The question is why? One answer is the rise of mental health issues. Which begs the question, why the rise of mental health issues? One of the answers you usually see is that the issues have always been there, but we are starting to better understand and recognize certain disorders; think PTSD, which for soldiers it used to be called shell shock, or combat fatigue and nostalgia.

There may be some truth to this statement, but it does not account for the rise in suicide. If mental health issues have always been there, and we have only come to better understand mental health disorders, why the rise in suicide that is said to be a mental health issue? Well, mental health issues are on the rise too, and it is not that we have simply come to better understand them. But I am not here to argue suicide as a mental health issue (though it is) I want to make the point that it is much more and predominantly a moral issue.

I will attempt to answer that question here, although it will not be complete. I will argue that it is not only a public health issue but also, and if not more importantly, a cultural, societal, philosophical moral question.

The poet and author G.K. Chesterton was a strong critic of suicide. He insisted that suicide is immoral, which seems strange to our ears because we have made it primarily a medical problem. Chesterton said, "It is the ultimate and absolute evil, the refusal to take an interest in existence; the refusal to take the oath of loyalty to life. The man who kills a man, kills a man. The man who kills himself, kills all men; as far as he is concerned he wipes out the world." Chesterton continues: "A suicide is a man who cares so little for anything outside him that he wants to see the last of everything."

Suicide as evil! Does this hit you hard? If Chesterton's use of evil makes you scratch your head, I venture to say you misunderstand the word evil. Evil is traditionally defined and understood as the privation of perfect goodness. Evil is only found in creatures (not things) as they depart from their good purpose, existing due to the corruption of free will. Evil thus is like darkness, the lack of light, evil being the lack of good. Suicide is therefore evil in the sense that it lacks goodness; it is a departure from what we are called for. This is easier to understand when you acknowledge the person with suicidal ideation longs for the good but is overwhelmed by darkness.

Our contemporary culture does not see suicide as evil but as a medical problem, a "public health concern," as the American Public Health Association (the worlds largest suicidal prevention organization) puts it,

“We are amid an unprecedented public health crisis, yet we also have an opportunity to come together to support one another and find ways to engage in meaningful conversations about mental health and wellness,”

I do not wish to downplay the importance of mental health or the fact that suicide is a public health concern. Still, if we are going to have meaningful conversations about suicide, we need to broaden our idea of suicide not as a public health concern exclusively.

If we are committed to helping people overcome suicidal ideation, we should maintain with Chesterton that suicide is a moral issue, not merely a clinical one.

Jennifer Hecht's book Stay: A History of Suicide and the Philosophies Against It, does exactly that. In this book, Hecht explores the complexities of suicide and discusses the moral arguments against it.

She argues that our conception of suicide is new and extreme and should not be accepted without question. We should instead challenge our understanding of suicide in light of past and current philosophy. In the very least, we should know what guides our conception of suicide. Hecht writes, "The arguments against suicide that I intend to revivify in public consciousness assert that suicide is wrong, that it harms the community, that it damages humanity, that it unfairly preempts your future self."

We have lost sight of the moral arguments against suicide, partly because the moralist were quick to condemn the victim of suicide to an eternity in hell and we were put off by such a simplistic understanding. But also because of ethical egoism and individual relativism. To better understand the teaching, or false teaching, rather, that someone who commits suicide is automatically going to hell, visit this article that I found most helpful.

Many have even begun to argue for the benefits of suicide. Here are the Top Reasons to Oppose Assisted Suicide

Getting back to these philosophical arguments will help prevent suicidal people from succumbing to their distress. They may begin to understand that suffering is a natural part of life that helps us develop into the person we want to become (if we allow it). In my article on the four levels of happiness, I mentioned that the lower forms of happiness (physical-material happiness and ego-comparative happiness) are the least pervasive, enduring, and deep. That reason would have us place more emphasis on the higher forms of happiness; happiness that involves more of the intellectual, creative, loveable, moral, spiritual, willful, self (contributive and loving/ transcendental happiness). Suffering then can liberate us from surface level happiness and living in a superficial deprivation - an even greater pain and loss. The first step with dealing with suffering is to bring fear, anxiety, pain, and negative emotions into perspective and how we can use our sufferings to bring us to a higher purpose, identity, and character strengths we value. I digress...

People with suicidal ideation must be encouraged to live not just for themselves but for others as well. This is precisely why suicide is a moral issue. It involves other people. No one commits suicide in isolation. Other people are always affected.

Hecht's brings to mind something known as "suicide cluster," where it is not uncommon to find people in the community to follow suit. Take for instance, the high suicide rate amongst veterans. You have the suicide forest in Japan and the "honorable" seppuku form of ritual suicide that originated with Japan's ancient samurai warrior class that involved stabbing oneself in the belly with a short sword, slicing open the stomach and then turning the blade upwards. These arguments alone go to show suicide has everything to do with culture and philosophy of life as it does mental health.

The very idea of suicide within a people can lead to a suicide cluster. Goethe's novel The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774) demonstrates this. It is a story of a young man who kills himself when his loved one rejects him. When it was published, it sparked a wave of copycat suicides in Europe, causing what is now known as the "Werther effect."

This is why we must be careful when it comes to popular culture, Hollywood, and our music.

We may be inadvertently pushing people to suicide by bringing it out into the light in the name of public health crises. Netflix's 13 Reasons Why in one such controversy.

I'll end with that we have to appeal to people with suicidal ideation's moral compass. At the most basic level, we experience an inclination to flourish. Springing out of this most basic desire to flourish is the desire for the good. We are moral creatures and there is no getting away from it. Unfortunately, modern secular psychology which believes values are viewed as relative to the individual only makes things worse for the person with suicidal ideation.

Every prominent modern psychology, from Freud to Jung to cognitive dissonance theory, assumes that the only good is what is good for the individual self. This view can take a variety of forms, ranging from moral philosophy of ethical egoism to individual relativism of a radical kind. The nature and consequences of these views are rarely acknowledged or defended (Vitz, Nordling, Titus, 2020, p 65).

One such consequence is the demoralizing of suicide. We have neglected to appeal and help those with suicidal ideation develop their most basic tendencies towards the good and have instead fostered the idea that for some people the only good for the individual self is to kill the individual self. The ethical egoist and moral relativist have no argument against it, that is, until they are unfortunately affected by it themselves. If you are looking for good philosophical moral arguments against suicide, if you have been affected by suicide or have contemplated suicide, Hecht's book comes highly recommended.

For more on how I might deal with a person who has suicidal ideation visit my blog post on Positive Psychology and What We Get Wrong About Depression.

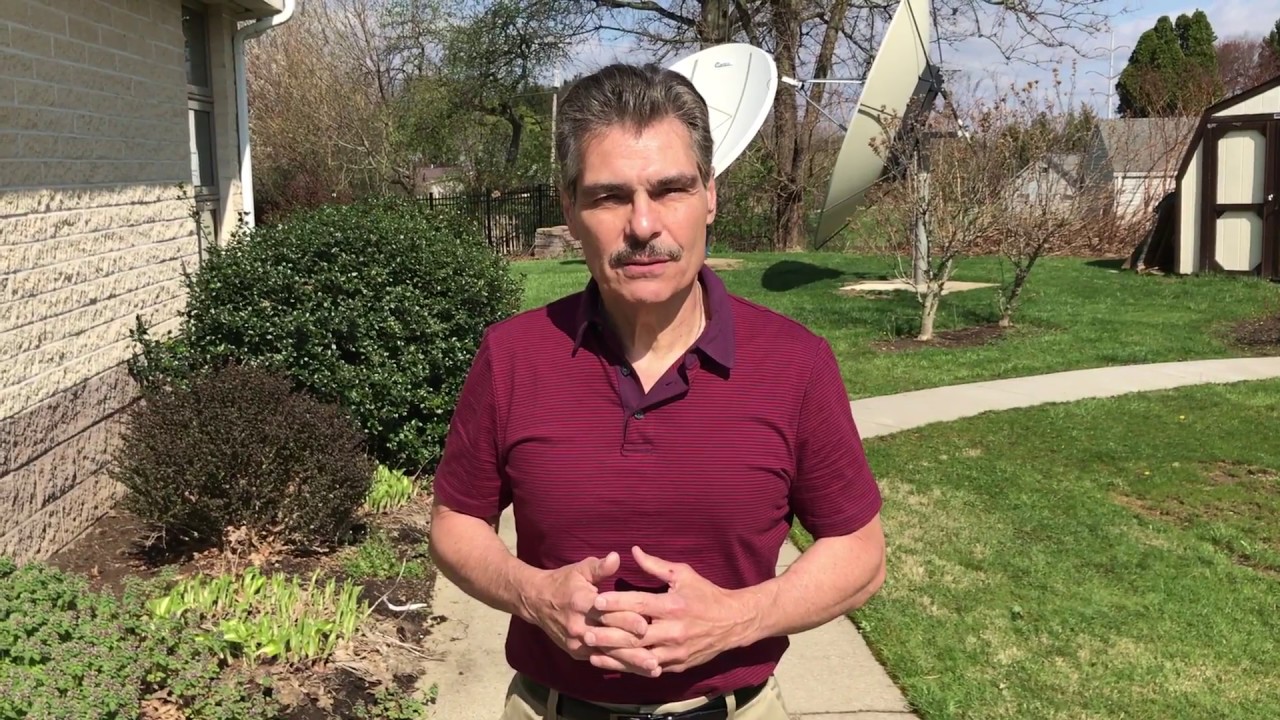

Odell Terrell

Odell Terrell is a mental health counselor in Greensboro, NC. He graduated with a MS in Counseling from Divine Mercy University in Arlington, VA, and places an emphasis on working with spiritual integration, adults and adolescents, trauma, family and children, and grief and loss. Odell received his undergraduate degree from the University of St. Leo's in St. Leo Florida, with a degree in Psychology. He has spent his last 15 years working in the field of emergency services. It is in working with people in emergency situations, both patients and first responders, that Odell has learned how to deal respectively with people in crises mode, helping instill a sense of hope and healing. Odell is happily married, for 17 years, and is the father of 9 children and brings a wealth of knowledge and experience to his family and child therapy practice.

Comments