Addiction: Disease or Choice? Or Something Different All Together?

- Odell Terrell

- Mar 14, 2022

- 4 min read

Addiction has come to be understood as either a medical disease or the opposite contrary view, a voluntary choice. But, according to Dunnington, addiction is not a disease or a bad choice, but rather an ingrained habit.

He argues in his book, "Addiction and Virtue: Beyond the Models of Disease and Choice,"

that if addiction is only a medical disease, people should not be able to recover independently of medicine. However, they do it all the time with the help of family, 12-step programs, and mental health treatment. In fact, few addicts recover solely through medical treatment alone. Most medically-based interventions work in tandem with other therapies.

The fact that many addicts can and do recover in a non-medical context

is what has led to the common assertion that addiction is a choice. "A person can simply will themselves out of their dependence."

Dunnington argues against this, as do I.

Addiction as habit:

A habit is formed when repeated voluntary actions over an extended period of time. Once the habit is formed, the actions that follow are often unconscious and involuntary. Thus, only addiction as habit can account for both addiction's involuntary and voluntary characteristics.

So why and how do people become addicted to begin with?

According to Aristotle, "every art and every inquiry, and similarly every action and pursuit, is thought to aim at some good; and for this reason, the good has rightly been declared to be that at which all things aim."

If true, then it should be just as true of habits and addictions [vice]. “Addictions are like virtues and vices in this respect, [in that] virtues and vices are habits that empower persons to pursue consistently, successfully and with ease various kinds of goods . . . habits through the practice of which human beings aim at the good life, the life of happiness” (Dunnington 96). The difference is that virtues lead to a life of fulfillment, vice does not.

The person plagued by addiction is pursuing a good, “like the ability to communicate, being at ease with oneself, being unafraid and being part of a community" (Dunnington 94). Additionally, people use because they are looking to self-medicate, reduce stress, fill a void in their lives, feelings of inadequacy, all of which show an inner longing for something good and ultimately a life of happiness.

This is important because when the appetites that underlie habits are ordered by right reason, they can lead to the good of the individual, for the good which the appetites pursue are real goods and so reason should take those real goods into consideration in the universal good of the individual.

It is necessary to help a person who suffers from an addiction to see the good they really long for that it can be attainable and even help aid them towards attaining it if need be. This is hard to do the more ingrained the habit has become because the passions have blinded the intellect. The intellect is drawn into the object of the passion rather than being free to make proper judgments. The brain chemistry has also changed so much to the point that you need to use just to feel normal.

Medication, detox, and rehabilitation may be necessary when it is serious enough, and biofeedback therapy helps those with substance abuse disorder regain control of their minds.

When combined with cognitive and dialectical behavior therapy you can see positive results. The ultimate goal is to help the client reduce stress and anxiety and reward the brain and appetite with more enduring, fulfilling goods of happiness.

This is where mental health therapists come in. Helping the client build a life of virtue through repeated counseling will help with addiction and make the psychological life more accessible because the appetites will become more trainable.

Even though the appetites have their own good and can fight against reason they are never the less trainable. The appetites are naturally ordered to obey reason. As the appetites quite repeatedly, they become less habituated.

In the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle lays out his idea of the “Good Life” and how to obtain it. For Aristotle, the Good Life meant living a life of virtue. Opposed to Plato and Socrates, Aristotle did not believe that understanding the virtues was enough to lead a virtuous life. The only way to become virtuous was to act virtuously.

"But the virtues we get by first exercising them, as also happens in the case of the arts as well. For the things we have to learn before we can do them, we learn by doing them, e.g., men become builders by building and lyreplayers by playing the lyre; so too we become just by doing just acts, temperate by doing temperate acts, brave by doing brave acts."

Virtues do not come from simply thinking about them. Aristotle assures us that if we want a virtue, we must act as if we already have it. Through exercise, our virtues will become ours. Change comes through action. Act first, then become.

If we are going to make the virtues a habit it is best to start where you are. Mother Teresa said, "if you want to change the world, start at home." Eventually, one habit will extinguish the other.

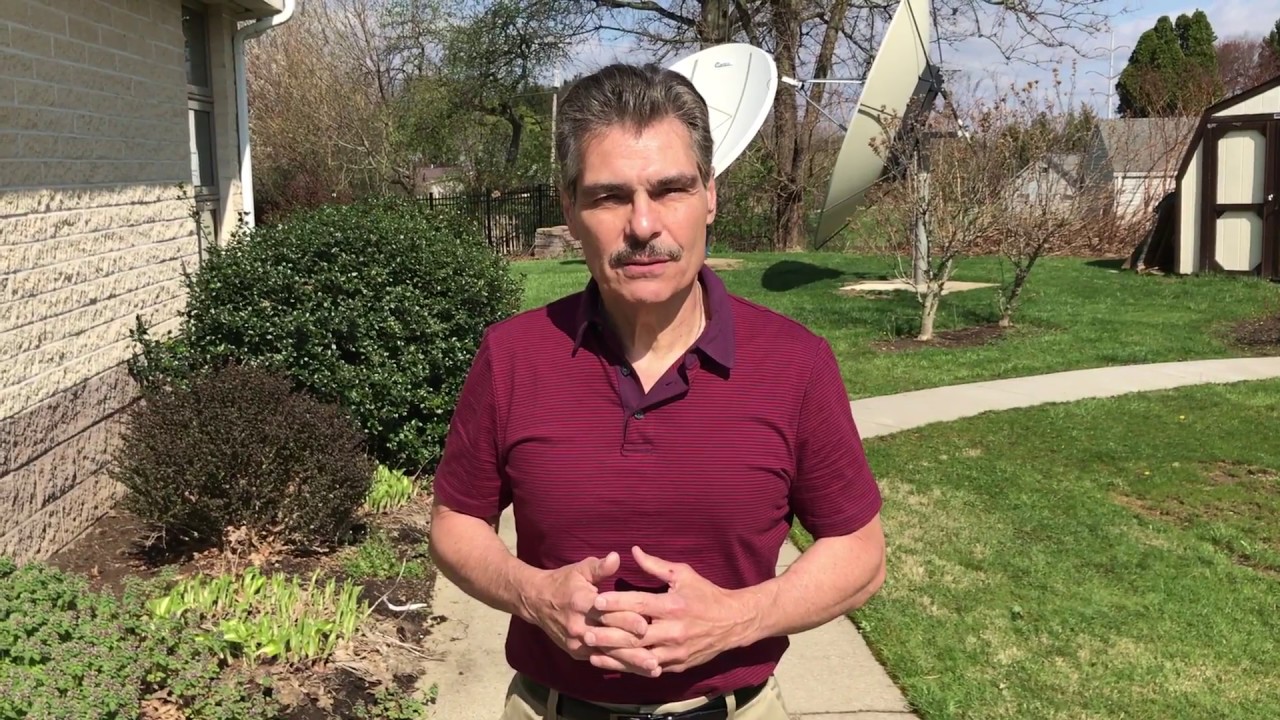

Odell Terrell

Odell Terrell is a mental health counselor in Greensboro, NC. He graduated with a MS in Counseling from Divine Mercy University in Arlington, VA, and places an emphasis on working with spiritual integration, adults and adolescents, trauma, family and children, and grief and loss. Odell received his undergraduate degree from the University of St. Leo's in St. Leo Florida, with a degree in Psychology. He has spent his last 15 years working in the field of emergency services. It is in working with people in emergency situations, both patients and first responders, that Odell has learned how to deal respectively with people in crises mode, helping instill a sense of hope and healing. Odell is happily married, for 17 years, and is the father of 9 children and brings a wealth of knowledge and experience to his family and child therapy practice.

https://rehabs.com/pro-talk/how-and-why-addiction-is-not-a-disease-a-neuroscientist-challenges-traditional-views/